She really paved the way for black women and minorities to play tennis . . . she was a forerunner.

—Venus Williams

Before Serena Williams. Before Venus Williams. Before Zina Garrison. Before Arthur Ashe and, switching sports, before Tiger Woods, there was Althea Gibson.

Gibson was the trailblazing mid-twentieth century black tennis player who desegregated the lily-white country-club environment then synonymous with the sport. Beyond being a pioneer, Gibson became a dominant champion, racking up 11 Grand Slam tournament victories during an astounding four-year stretch from 1956 to 1959.

And for good measure, when the powerful, 5-foot-11 athlete concluded her tennis career, she took up golf. Here again, she bucked discrimination and competed in a sport that had mostly been a whites-only endeavor, becoming the first African American woman to play on the Ladies Professional Golf Association circuit.

Gibson achieved all this from humble roots. Born in rural Silver, South Carolina, the daughter of poor cotton sharecroppers, Gibson would ultimately come to chat with Queen Elizabeth; cut an album; sing, twice, on The Ed Sullivan Show; play a saxophone given to her by two of her mentors, the boxer Sugar Ray Robinson and his wife, Edna Mae; and costar in a John Ford western with John Wayne.

Starting a Racket

School wasn’t a priority for Gibson as a child. Growing up in New York City’s Harlem (where her family moved when she was three), Gibson was more focused on sports, especially basketball and table tennis, than her studies. At 14, she abandoned her paddle when a friend of the family gave her a tennis racket, and she turned out to be a natural: swift, strong and savvy.

Gibson found her new passion, left high school behind and started competing in local girls’ tournaments. Her ability quickly caught the attention of two local tennis patrons: Dr. Robert W. Johnson, who would later help Ashe and others, and Dr. Hubert Eaton. Both were impressed with her skills on the court, and Eaton eventually brought Gibson to live with his family in Wilmington, North Carolina, to help with her training. Eaton placed Gibson, the dropout, back in high school, and he provided square meals, tennis instruction and a practice court.

The move proved fruitful: Gibson excelled in her new surroundings, playing saxophone in the school marching band and earning a college scholarship to attend Florida A&M University. But moving from New York City to the South, where Jim Crow legislation separated whites from “persons of color” in many public settings such as schools and public transportation, was a culture shock for the young woman. Gibson, for example, had to ride in the back of buses for the first time in her life.

“I was burned up that I had to conform to such an ignorant law,” she said.

During summers, Gibson went to Virginia to live with the Johnsons. She and Dr. Johnson played mixed-doubles matches on the American Tennis Association (ATA) circuit. Together, they won eight of nine tourneys. In the singles bracket, Gibson went nine for nine.

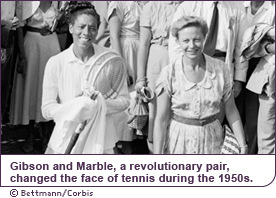

The ATA was all black, a far cry in national prestige and purse money from the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA), the whites-only loop. Black and white supporters urged the USLTA to permit Gibson entry, but it wasn’t until Alice Marble, a white tennis star, came forward to champion Gibson’s cause that the association responded.

Marble, 14 years Gibson’s senior, wrote a furious open letter, which was published in the July 1950 issue of the association’s magazine. “She is not being judged by the yardstick of ability,” Marble wrote, “but by…her pigmentation.” The USLTA relented.

Hitting the Grand Slam

In 1950, the USLTA permitted Gibson to enter the U.S. Nationals, later known as the U.S. Open. Gibson took the D and the F subway lines to the stadium in Queens, traveling with a gym bag and two rackets.

In 1950, the USLTA permitted Gibson to enter the U.S. Nationals, later known as the U.S. Open. Gibson took the D and the F subway lines to the stadium in Queens, traveling with a gym bag and two rackets.

The determined athlete defeated her first-round opponent, then showed great skill on the court against Louise Brough, her highly regarded second-round draw. Gibson was leading when a thunderstorm hit. The match reconvened the next morning, and Brough won.

Gibson was then invited to play the next year in London, at Wimbledon, tennis’ most prestigious competition. With great supporters like Joe Louis, the heavyweight champ, she was able to raise training and travel money. Unfortunately, her first Grand Slam title was far from reach. Gibson went as far as the third round.

During the next six years, Gibson periodically played USLTA events, but failed to win. She accepted a physical-education job, thinking of quitting tennis.

Then, as luck would have it, the U.S. State Department asked Gibson to join three other players on a goodwill exhibition tour of Burma, Thailand, Ceylon, India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Gibson accepted and the voyage revitalized her.

A Prevailing Stretch

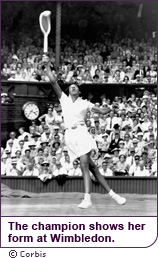

Gibson finally found her rhythm, dominating the sport during the second half of the 1950s. She utilized an aggressive serve-and-volley style to overwhelm shorter opponents. She won each of tennis’ four major Grand Slam tournaments and collected a series of sociological “firsts”: first black person to win a Wimbledon title (the 1956 doubles crown); first to win the French Open in both singles and doubles (1956); first to win the doubles title at the Australian Open (1957) and first to win the U.S. Open (1957).

With tennis’ color barrier broken, Gibson the player kept on smashing, winning the Wimbledon singles and doubles title in 1957 and 1958. In 1957 Gibson was so confident that she penned an acceptance speech in advance and packed an evening gown for the victory party.

With tennis’ color barrier broken, Gibson the player kept on smashing, winning the Wimbledon singles and doubles title in 1957 and 1958. In 1957 Gibson was so confident that she penned an acceptance speech in advance and packed an evening gown for the victory party.

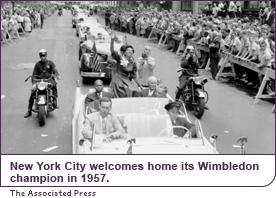

New York City celebrated the Harlem athlete’s 1957 win with a ticker-tape parade.

Gibson rode in a white convertible as confetti rained down on her checkered dress and corsage. The mayor even presented Gibson with the city medallion.

Iron Will

When Gibson’s tennis victories dropped off dramatically in the early 1960s, she found an easier sport for an aging body—Gibson took up golf.

She joined the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) as its first black member. Gibson played from 1964 to 1970, ultimately remembered more as a groundbreaker than a superb player.

In 1971, 30 years after picking up her first racket, Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Off the court and the green, she served as a spokesperson for a bakery company, and, from 1975 to 1992, she was appointed to various New Jersey state athletic commissions. The multitalented Gibson also dabbled in acting, singing and writing.

She left the public eye in the 1990s, retreating to her East Orange, New Jersey, home and suffering for years from strokes and other effects of an undisclosed terminal illness. In an unfortunate end to an incredible life, Gibson died, broke and reclusive, in September 2003. A year later, the U.S. Open memorialized her with an Althea Gibson Day.

Bud Collins, tennis’ bard, took the occasion to write an appreciation of Gibson in The Boston Globe.

“Tennis is a lonely game at the upper reaches where self-belief is the life raft,” Collins wrote. “Reaching for that level, especially when you know you aren’t exactly welcome, is daunting. But Althea Gibson out of Harlem fit her destiny splendidly.”

As Gibson herself put it in 1956, “I am just another tennis player. Not a Negro tennis player.”

:: woa.tv staff

Read More About Althea Gibson