She was the lady who most changed the style of play for women. She introduced the aggressive and athletic style that has led to the female stars of today.

—Jack Kramer, tennis player

Long before the era of million-dollar tourneys and big endorsement deals, tennis players such as Suzanne Lenglen, Helen Wills Moody, Helen Jacobs and Alice Marble rivaled Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey in front-page headlines. In the 1920s and ’30s, women’s tennis was a world filled with flamboyant characters who flouted social conventions. Think Serena Williams caused controversy with her denim tennis skirt and boots at the 2004 U.S. Open? Lenglen’s short skirts provoked mass  outrage back in the day—and they were calf-length. And Alice Marble had the audacity to don shorts on the courts—the first female player ever to do so in a professional tennis match. This bold move, coupled with her good looks, immediately made Marble popular with the press and legions of tennis fans. But what really kept the crowds mesmerized was the way Marble moved on the court.

outrage back in the day—and they were calf-length. And Alice Marble had the audacity to don shorts on the courts—the first female player ever to do so in a professional tennis match. This bold move, coupled with her good looks, immediately made Marble popular with the press and legions of tennis fans. But what really kept the crowds mesmerized was the way Marble moved on the court.

With her all-out attack on the ball and daring charges to the net, she played in a style considered “masculine” at the time—her smash alone was considered revolutionary. As the first serve-and-volley player in women’s tennis, Marble proved that women could play tennis with as much power and fervor as men. Until Martina Navratilova hit the circuit about four decades later, no other woman played “big game” the way Marble did.

Her First Love

Tennis wasn’t Marble’s first passion—what she really wanted to play was baseball. As a kid, she spent every summer day at the ballpark watching the San Francisco Seals (the predecessors to today’s S.F. Giants) practice. One day, as she and her brother played catch in the bleachers, her favorite player, Lefty O’Doul, tapped Marble (thinking she was a boy) to retrieve flies. From centerfield, Joe DiMaggio shouted words of encouragement, and the catcher of the team decided then and there to recruit her. She soon became the official mascot of the team and warmed up the Seals’ famous bench before every game.

When her older brother suggested she stop being such a tomboy and take up tennis instead, Marble responded with similar machismo, shouting, “I won’t play that sissy game!”

The baseball fan, however, picked up a racket. Her parents favored tennis and disapproved of their 15-year-old daughter playing baseball with boys. They got their wish and Marble found her true calling. Maybe it was her initial impression of tennis that led her to infuse aggression and power into her play, making it less a game of dull rallying. Marble played to win. And though she had little formal training, her natural athletic abilities made the transition to the game easy, and all that early pitching practice made for one mean serve.

But tragedy struck the young athlete soon after she started playing. Marble was attacked and raped by a man at the Golden Gate tennis courts. (He was never identified.) Later in life she credited tennis as helping with the recovery of her self-esteem, and the horrible incident as a factor in the development of her trademark mental toughness.

But tragedy struck the young athlete soon after she started playing. Marble was attacked and raped by a man at the Golden Gate tennis courts. (He was never identified.) Later in life she credited tennis as helping with the recovery of her self-esteem, and the horrible incident as a factor in the development of her trademark mental toughness.

From that point on, Marble’s career was hampered by fits and starts due to health problems and the advent of World War II. At first, she rose quickly up the amateur ranks, taking her place in the world’s top ten in 1933. Then a series of setbacks, including a misdiagnosis of tuberculosis, kept her off the courts for three years.

When she returned to competition in 1936, she did so with a vengeance. With her new coach, Eleanor Tennant, and new grip (she switched to eastern style), Marble played at Forest Hills that year and won the U.S. crown. After that she pretty much dominated the game for the rest of the decade: three singles titles, four doubles titles and four mixed doubles titles at the U.S. Open and one singles title, two doubles titles and three mixed doubles titles at Wimbledon. It’s no wonder Associated Press named Marble Female Athlete of the Year in 1939 and 1940.

Alice Marble was a picture of unrestrained athleticism. She is remembered as one of the greatest women to play the game because of her pioneering style in power tennis. I also admire her tremendously because she always helped others.—Billie Jean King

From Racket to Racketeers

After all the accolades, Marble turned professional (since this was before the sport’s Open Era the move effectively ended her competitive career), and her fame continued to grow. During the war she played exhibition matches and taught clinics on military bases. At one such exhibition, she got a little more “love” than she bargained for when she met Joe Crowley, a soldier who became her husband. But their marital bliss didn’t last. In 1944, Marble was in a car accident that caused her to miscarry a pregnancy and, just days later, her husband was killed in combat overseas.

Not long after these tragedies, U.S. Army Intelligence approached Marble with an unusual request. An ex-lover of hers was laundering money for the Nazis in Switzerland. Marble, never one to back down from a challenge, volunteered for duty immediately and was sent to Switzerland as a U.S. spy. While the details about this assignment are sketchy (it was espionage, after all), some accounts hold that Marble was shot in the back while on her mission and rescued by a military intelligence contact.

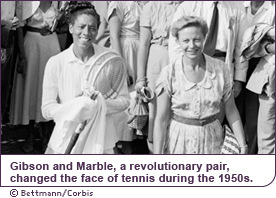

Apparently, not even a bullet could stop Marble, and after her service in the war, she returned to tennis as a coach. In the 1960s, she taught an upstart named Billie Jean King, but this tutelage was not her most lasting mark on the sport. Instead, it was Marble’s staunch support of Althea Gibson, the first African American woman to compete at a national championship (Gibson not only competed, she eventually won—count ’em—11 Grand Slam titles), which changed the game forever.

In the 1950s, segregation was still strongly supported on the tennis courts, and, because of her race, Gibson was limited to playing matches in the all-black American Tennis Association (ATA) league. Grand Slam tournaments such as Forest Hills and Wimbledon weren’t even an option for the skilled player, but Gibson cleaned up in the ATA, winning the singles championship ten years in a row. Despite her obvious skill, Gibson still wasn’t allowed to move up to a more competitive level—that is, until Marble stepped in.

The powerhouse player emerged as an equally influential activist. Marble effectively shamed the tennis establishment in an open letter she published in American Lawn Tennis magazine that stated: “If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it’s also time we acted a little more like gentle people and less like sanctimonious hypocrites. If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of women players, it’s only fair that they should meet the challenge on the courts.”

The powerhouse player emerged as an equally influential activist. Marble effectively shamed the tennis establishment in an open letter she published in American Lawn Tennis magazine that stated: “If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it’s also time we acted a little more like gentle people and less like sanctimonious hypocrites. If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of women players, it’s only fair that they should meet the challenge on the courts.”

The article did the trick and Gibson was finally invited to play at Forest Hills that year, and at Wimbledon a year later. From there, Gibson started dominating the sport on her own, but without Marble as her advocate, one of the premiere players of the twentieth century may have never entered the Grand Slams.

Tennis champ, American spy and activist—not a bad legacy for a gal who just wanted to play baseball.

:: woa.tv staff

Read More About Alice Marble