Mariel Zagunis wasn’t supposed to even be in Athens. The 19-year-old fencer had been added to the U.S. Olympic team only after the Nigerian Olympic Committee decided not to have its fencer participate in the competition. Now Zagunis found herself in the final bout of the 2004 Olympic women’s sabre competition, dueling for the gold medal.

Facing China’s Xue Tan, a former world champion, the young hopeful started smartly, charging in against her opponent to score the first touch. She continued to move quickly, gaining a 9-2 lead. Midway through the match, Tan, who’d previously disposed of the expected gold-medal winner (Zagunis’ teammate Sada Jacobson), gained momentum and seemed poised for a comeback. Zagunis fought hard to keep her control, mixing defensive and offensive moves and throwing out every skill she’d gathered in her nine years of training. Finally, she landed a string of cunning and ruthless attacks. It was over. Tan had been defeated, 15-9.

Facing China’s Xue Tan, a former world champion, the young hopeful started smartly, charging in against her opponent to score the first touch. She continued to move quickly, gaining a 9-2 lead. Midway through the match, Tan, who’d previously disposed of the expected gold-medal winner (Zagunis’ teammate Sada Jacobson), gained momentum and seemed poised for a comeback. Zagunis fought hard to keep her control, mixing defensive and offensive moves and throwing out every skill she’d gathered in her nine years of training. Finally, she landed a string of cunning and ruthless attacks. It was over. Tan had been defeated, 15-9.

Pulling off her mask and throwing back her head, Zagunis let out a victorious scream. Teammates surrounded, grabbing hold and tossing her into the air like a toddler. The ecstatic Zagunis grinned. She hadn’t just won the first gold medal in women’s sabre. She had won the United States’ first fencing gold medal in 100 years.

Few expected women’s sabre to be a prime-time Olympic event in 2004. As the Zagunis drama unfolded, however, captivated viewers became witness to the participants’ intense and demanding physical moves and complex strategizing. Long regarded in pop culture as an elitist sport of dilettantes, fencing is actually as physically demanding as sports such as basketball, soccer and tennis, requiring stamina, drive, concentration and the ability to think creatively and quickly. Also, since the fencing weapon’s tip is the second-fastest moving object in sport (the first is the marksperson’s bullet), a fencer must have quick reflexes and be in top physical condition to avoid taking a hit during a bout.

Unlike the stereotype of chivalrous fencers who duel politely, real fencers are a raucous bunch, known for banshee-like shrieks on the strip, screaming after touches to release adrenaline—and perhaps to influence judges’ calls. Though fencing is a competitive sport today, the primal sounds that surround a major competition hark back to the discipline’s origins, when the sword was used in duels to the death.

From Combat to Sport

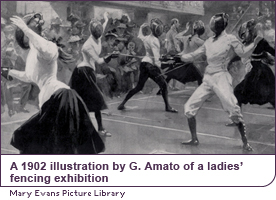

Fencing, or the art and skill of fighting with a sword, has been practiced throughout the world for centuries. Ancient Romans and Greeks incorporated swordsmanship into military training, and warriors around the world fought with swords in battle. The invention of the gun around the year 1500 changed the nature of fencing. Since this new weapon could penetrate heavy armor, the sword evolved into a secondary weapon, mostly reserved for duels.

Fencing, or the art and skill of fighting with a sword, has been practiced throughout the world for centuries. Ancient Romans and Greeks incorporated swordsmanship into military training, and warriors around the world fought with swords in battle. The invention of the gun around the year 1500 changed the nature of fencing. Since this new weapon could penetrate heavy armor, the sword evolved into a secondary weapon, mostly reserved for duels.

In the 1800s, dueling was generally outlawed. Too many people had died from dueling, and it was felt that the salles d’armes, or fencing schools, attracted an unsavory element. So the salles turned to teaching fencing for sport, not combat.

The sport’s objective is for one’s opponent to be touched (touché) with the weapon (as opposed to penetrated, which would be the objective in a duel or during combat). There are three weapons: foil, épée and sabre. Each blade requires slight variations of style, technique and rules. Also, each weapon has a different scoring target. For the épée, it is the entire body; for the foil, the torso; and for the sabre, it is the body from the hips up, including the arms and mask.

Fencing became an organized competitive sport in the late 1800s. Dr. Adelaide Baylis won the first U.S. women’s foil national championship in 1912, and in 1929 three collegiate fencers, Julia Jones, Dorothy Hafner and Elizabeth Ross, founded the National Intercollegiate Women’s Fencing Association (NIWFA) to encourage women’s fencing. That same year, in Naples, Italy, a women’s foil competition was added to the European championships.

Today, women fence with all three weapons and compete individually as well as in teams. The Fédération Internationale d’Escrime (FIE) sanctions all international competitions and hosts an annual world championship. In the United States, the U.S. Fencing Association (USFA) organizes competitions for athletes of all ages, except collegiate competitors, whose competition is governed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The sport’s most important competition takes place at the Olympic Games, where women’s individual foil debuted in 1924 with bouts to five touches (as in the men’s event) but with a smaller target area (the groin was not a valid target for women until 1960, by which point fencing in trousers had become common for women). A team foil event was introduced for female fencers in 1960; épée, both individual and team, in 1996; and finally, sabre, generally considered to be the most aggressive form of fencing, in 2004.

About the Bout

A competition between two fencers is called a bout; the first fencer to land a hit on her opponent gains the point. Bout lengths and the number of touches needed to win vary.

A competition between two fencers is called a bout; the first fencer to land a hit on her opponent gains the point. Bout lengths and the number of touches needed to win vary.

Female fencers, like their male counterparts, wear protective gear, including a fencing jacket, a wire-mesh or Plexiglas mask, leather gloves, knee-length trousers, stockings and underarm protectors. These typically all-white uniforms are required at all levels of competition. And they aren’t worn just to make competitors look intimidating—though quaintly called “touches,” hits often leave dark bruises and cuts on a fencer’s body. For gender-specific protection, men wear athletic cups and women don breastplates. The uniforms are high-tech too: Because fencing action often occurs at high speeds, swords and uniforms are electrically wired to register hits and communicate with the scoring machine.

Bouts begin with the fencers in the on-guard (en garde) stance, standing so far apart on the piste that a lunge is required to reach the opposing fencer.  One fencer attacks, threatening the opponent with a thrust. This move establishes the fencing right-of-way; the other fencer is put in a defensive position and must deflect (or parry) the attacking blade. Once the defender makes the parry, she claims right-of-way and becomes the new attacker by returning (or riposting) the attack. In foil and sabre, fencing right-of-way alternates back and forth. Épée does not use right-of-way.

One fencer attacks, threatening the opponent with a thrust. This move establishes the fencing right-of-way; the other fencer is put in a defensive position and must deflect (or parry) the attacking blade. Once the defender makes the parry, she claims right-of-way and becomes the new attacker by returning (or riposting) the attack. In foil and sabre, fencing right-of-way alternates back and forth. Épée does not use right-of-way.

A competitor wins a bout by being the first to score a particular number of points or by having a higher score than her opponent when the time is up.

Blades Are All the Rage

Within the last few years, several exciting developments have helped to popularize fencing, especially among women. The first advancement was the development of new transparent masks, which heighten the drama of a bout by allowing match viewers to better see the participants’ expressions.

Secondly, the introduction of a women’s sabre event at the 2004 Athens Olympics led to enormous growth in the discipline. Now, there are approximately as many women sabrists as there are female competitors in the sport’s most popular discipline, foil. Within a year of the 2004 Olympics, where two U.S. women sabrists medaled, overall participation in the USFA was up 20 to 25 percent.

Secondly, the introduction of a women’s sabre event at the 2004 Athens Olympics led to enormous growth in the discipline. Now, there are approximately as many women sabrists as there are female competitors in the sport’s most popular discipline, foil. Within a year of the 2004 Olympics, where two U.S. women sabrists medaled, overall participation in the USFA was up 20 to 25 percent.

In the United States, there are almost 30,000 fencers registered to compete, and 34 percent of them are women. The FIE estimates that there are approximately 1 million fencers worldwide and that almost half of them are women. Shattering any notion that the female is the gentler sex, women fencers have carved a raucous path: lunging, slashing and screaming their way into sports history.

:: Maureen Russell

Read More About Fencing