Modern dance isn’t anything except one thing in my mind: the freedom of women in America.

—Martha Graham

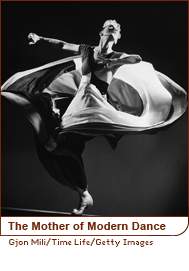

Martha Graham’s impact on the dance world has often been compared to Picasso’s impact on the art world; she revolutionized modern performance with her gutsy blend of percussive movements and abstract expression. In the early twentieth century, Graham was one of the first choreographers to collaborate with other artists to create visually stunning productions, making some of the most daring, creative performances in dance history. She also radically changed movement theory, and the effects of her innovations are visible today in every discipline of the performing arts.

Girl on the Move

In 1908, at the age of 14, Graham moved with her family from Allegheny, Pennsylvania, to Santa Barbara, California. She was an active, athletic child, but did not come to dance until well past her teens—dangerously late for a dancer to start her training.

In 1908, at the age of 14, Graham moved with her family from Allegheny, Pennsylvania, to Santa Barbara, California. She was an active, athletic child, but did not come to dance until well past her teens—dangerously late for a dancer to start her training.

After seeing modern dancer Ruth St. Denis in a performance at Los Angeles’ Mason Opera House in 1911 (“That night my fate was sealed,” Graham said), she enrolled in a junior college specializing in the arts, and then in the new Denishawn School of Dance, founded by St. Denis and her husband, dancer Ted Shawn. There, Graham studied American and world dance. Though St. Denis thought of her as “too old, small and not particularly attractive,” Graham quickly rose from student to celebrated performer, earning critical acclaim when she gave an explosive performance in Denishawn’s Xochitl, based on an Aztec legend about an emperor.

After seven years at Denishawn, Graham headed east for New York. To make ends meet, she danced in a vaudeville show called The Greenwich Village Follies and gave modern-dance classes at the Eastman School of Music. She was given complete control over the dance program at Eastman, and she used the opportunity to hone her skills as a choreographer. Finally ready to break out on her own, in 1926, she started presenting solo and trio performances at the 48th Street Theater.

Declaring Her Independence

One of her greatest accomplishments was to look at the patriarchal mythology from the feminine viewpoint.

—Joseph Mazo, dance critic

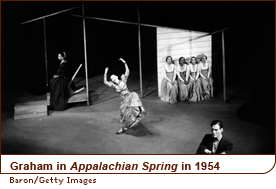

In 1929, with some of her Eastman students, Graham founded the now famous Martha Graham School for Contemporary Dance in New York. She then took on the very soul of the American woman, beginning with the performance of Frontier (1935), an exploration of the pioneer spirit, and going on to produce remarkable dance portraits of strong women on the verge of a new life, including one of her most famous pieces, Appalachian Spring (1944), which featured a score by renowned composer Aaron Copland.

She also tackled the likes of Emily Dickinson (Letter to the World, 1940) and the Brontë sisters (Deaths and Entrances, 1943). And in her great works drawing on Greek mythology, she gave life to Medea, as well as to other female characters from Greek mythology, Clytemnestra, Phaedra and Jocasta. She even produced performances inspired by Joan of Arc and Mary, Queen of Scots!

“All things I do are in every woman,” Graham said. “Every woman is Medea. Every woman is Jocasta.”

It was only fitting that as a choreographer-dancer who honored heroic women, Graham, too, would take a political stand in the international arena. When asked to perform at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, she refused, replying, “I would find it impossible to dance in Germany at the present time. So many artists whom I respect and admire have been persecuted, have been deprived of the right to work for ridiculous and unsatisfactory reasons, that I should consider it impossible to identify myself, by accepting the invitation, with the regime that has made such things possible.”

It was only fitting that as a choreographer-dancer who honored heroic women, Graham, too, would take a political stand in the international arena. When asked to perform at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, she refused, replying, “I would find it impossible to dance in Germany at the present time. So many artists whom I respect and admire have been persecuted, have been deprived of the right to work for ridiculous and unsatisfactory reasons, that I should consider it impossible to identify myself, by accepting the invitation, with the regime that has made such things possible.”

Starting a Revolution

Though embraced in the contemporary dance world, Graham’s movements were controversial when they first appeared on the stages of New York. The Western female dancer was traditionally associated with the soaring, graceful lines of classical ballet or, in the burgeoning world of modern dance, with a decorative, exoticized form of “ethnic” dancer.

The percussive movements, flexed feet and pelvic energy of Graham’s movement vocabulary bewildered some critics and audience members. Some thought the “contraction and release” fueled by what Graham called “the house of pelvic truth” was sexy, and others claimed that it lacked the lyrical grace of classical ballet, and called it downright ugly. Her movements were earthbound and jagged, expressive and fierce. Graham was changing the whole notion of dance, and the art form would never be the same after her.

She was an active participant in the flourishing movement of modern art, and she embraced all the excitement around her. She saw her ballets (ultimately, 128 of them) as complete pieces, and she was intimately involved in every aspect of production, including costume and set design and the composition of original scores.

She was an active participant in the flourishing movement of modern art, and she embraced all the excitement around her. She saw her ballets (ultimately, 128 of them) as complete pieces, and she was intimately involved in every aspect of production, including costume and set design and the composition of original scores.

The cornerstone of Graham’s technique was that her productions always originated in a primal, expressive movement. From there, Graham added a striking visual environment, often collaborating with Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Together, the two took bold new approaches to set design, replacing flat, painted backdrops with sculpture and three-dimensional landscapes.

Graham danced throughout most of her adult life, finally retiring from the stage in 1970. She continued as director of the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, teaching and choreographing until she died in 1991.

Through the Martha Graham Dance Company, Martha Graham Ensemble and the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance, her legacy lives on, and through her protégés, who are vital forces in the world of dance today. Alvin Ailey, Twyla Tharp, Paul Taylor and Merce Cunningham are among the many who are indebted to Graham’s genius.

:: Nora Pierce

Read More About Martha Graham