Long before the era of girl power, 17-year-old Joan of Arc led armies of men to victory against the English in order to liberate her country. The young warrior was headstrong enough to believe the voices of angels who told her a mere girl could save France. Joan would break many social codes on her mission, including boldly addressing authority figures and donning men’s clothing, a defiance that contributed to her tragic death at the young age of 19. But centuries later, the memory of Joan of Arc’s heroism lives on. No other teenage warrior in history has inspired the world quite like she has.

Miraculous Beginnings

Joan was one of five children born to farmer Jacques d’Arc and his wife, Isabelle. Her family lived in the village of Domrémy, where Joan was known as a deeply pious girl who attended mass daily. Even in heavily Catholic Domrémy, her religious fervor set her apart from most girls her age.

She grew up in the midst of the Hundred Years’ War between France and England. France was split into two factions: the Burgundians, who supported an alliance with England, and the Armagnacs, who fought for French sovereignty. Divided by civil war, France became even more vulnerable to invading English troops.

Joan’s family and most of Domrémy supported the dauphin, Charles. This meant frequent skirmishes with nearby Burgundians. Little did her family know how intimately involved their daughter would be in future battles.

When Joan was 13, she was praying in her father’s garden when she first saw a brilliant light and “received revelation from Our Lord by a voice which told [her] to be good and attend church often and that God would help [her],” according to her trial transcripts. From that day on, Saint Michael the Archangel, Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret spoke to Joan on a regular basis.

Rebel With a Cause

At 16, she was hearing the angels’ voices every day. They were telling her to “go into France” to assist the dauphin in claiming the throne and drive the English from the land. Joan pleaded with the saints, asking how she, a young, poor girl with no experience in riding or fighting, was to do such a thing. But the voices remained adamant.

In 1428, Joan followed their instructions and persuaded her uncle to take her to Lord Robert de Baudricourt, captain of the garrison at Vaucouleurs, ten miles north of Domrémy. Baudricourt refused an audience with Joan, and she returned home. Then, Domrémy was raided by Burgundian troops. The villagers took refuge in Neufchâteau.

By October, Orléans, the last major city in Charles’ domain, was besieged by English troops. Joan returned to Lord Baudricourt. This time, considering he had no other options, he granted the peasant an audience. She persuaded him to provide her with an escort to the castle at Chinon, where Charles, surrounded by enemies on all sides, had retreated to await final defeat.

Fierce Maiden

In preparation for her journey, Joan cut her hair and donned men’s clothes—partly as a disguise and partly to hide her body from the desiring gaze of her fellow soldiers. Thus armored, she swore herself to virginity for as long as her crusade should last, and dubbed herself “La Poucelle” (The Maiden).

She arrived at Chinon in March 1429. She walked directly up to Charles and addressed him boldly: “Most illustrious Dauphin, I have come and am sent in the name of God to bring aid to yourself and to the kingdom.” She demonstrated her link with the divine in several ways, including repeating the words of a prayer that he had said mentally. Now convinced that this girl possessed divine inspiration, Charles still felt it necessary to subject her to a rigorous examination by priests to prove her adherence to established doctrine. Joan aced the examination.

Confident in the young girl’s conviction, Charles gave her an army and supplied her with a horse, a sword and a custom-made suit of armor. She refused the sword, saying her weapon lay behind the altar of the Church of Sainte Catherine de Fierbois. A guard was dispatched to retrieve it. He returned with a sword marked with five crosses upon the blade, which he had found exactly where she had said it would be. With sword in hand, Joan set out to save Orléans, which had been under siege by the British for six months.

Joan sent two letters to the English by messenger, calling for their surrender. Receiving no reply, she sent a final letter that read, “Leave your fortress and go back to your own country, or I will produce a clash of arms to be eternally remembered.”

Joan Kicks Buttresses

On May 6, Joan led an army of more than 4,000 men in her first battle. The target was a fortified monastery in Orléans. Joan rode gallantly ahead of her troops, encouraging them over the walls. On the second day of the siege, the French army captured two more English fortresses, but Joan was hit by an arrow while scaling a ladder. Frightened and in pain, the young leader was shaken by the reality of warfare. Despite her injury and newfound fear, she quickly returned to the field to lead her army in a final push toward victory.

Joan returned to Chinon after her success in Orléans and was embraced by her fellow officers. Her next mission was to lead Charles through three hundred miles of enemy territory for his coronation at Reims. Again, she proved an apt military leader, driving the English out of every town she entered. Her legend traveled even faster than her forces, and word of her victories spread throughout the French army, spurring further conquests. Her army swelled with soldiers wanting to fight under her banner. Her men believed that the angels accompanied them into battle. Her reputation even influenced the enemy: One English army unit, upon hearing of her approach, turned and fled without a fight.

Reims opened its gates to Joan on July 16, 1429, and on July 17, she stood by Charles’ side at his coronation. La Poucelle had accomplished her divine mission and crowned her king.

But this didn’t stop the Burgundian army, which continued to fight in support of the English. Joan’s forces returned to the battlefield, at first continuing their string of victories. Unfortunately, Joan was finally captured by Burgundian troops in 1430, when she was pulled from her horse in Compiègne. She was taken to Rouen, the seat of the occupation government, and turned over to church officials for money.

Joan, Interrupted

Joan was taken to prison, where she would await trial. Since she was going to be tried in an ecclesiastical court, Joan should have been held in a church prison, guarded by women. Instead, she was shackled in leg irons and thrown in a military prison, surrounded by hostile men. Joan insisted on keeping her men’s clothes, in part to demonstrate loyalty to the voices of “God and the angels” above obedience to worldly authorities, and in part because in this attire she felt less vulnerable to sexual assault by male guards. This insistence on cross-dressing led to her eventual demise.

Her trial began on January 9, 1431, and was engineered by Pierre Cauchon, a toady of the Anglo-Burgundians. With a jury of corrupt clergy and a trial paid for by the English government, officials sought to discredit Joan with an accusation of heresy. On May 24, after a long, grueling trial, Joan was threatened with summary execution. Sick and terrified, she relented and signed a “confession”—and also agreed to wear a dress.

But the devious Cauchon had manufactured a trap. After suffering several rape attempts by her guards as well as by a lord, Joan was stripped of her dress and given back her forbidden men’s clothes. She was forced to either remain naked or recommit the crime of wearing men’s clothing. She chose the latter and was convicted of being a “relapsed heretic.” She was sentenced to death by burning.

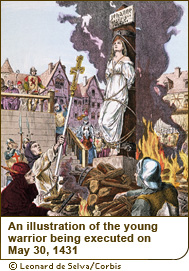

On May 30, 1431, Joan of Arc was executed in the square at Rouen. Eyewitnesses say she listened quietly to a sermon. Then, weeping, she asked forgiveness for her accusers. Most of the judges and a few of the English soldiers and officials were sobbing by the end of her speech. Still, they tied her to a pillar in the center of a woodpile and lit a fire beneath her. A Dominican monk held up a crucifix for her to look at as the flames engulfed her. She screamed the name of Jesus several times before her head dropped to her chest. Joan was 19 years old when she died.

Divine Retribution

It wasn’t until about two decades later that the English were finally driven out of Rouen and an appeals trial was conducted on Joan’s behalf. The court ruled that she had been convicted illegally by a corrupt court. She was exonerated and described as a martyr. And five centuries later, on May 16, 1920, she was canonized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

From peasant girl to Catholic saint, Joan’s short yet extraordinary life continues to inspire generations of women to fight for their beliefs, and reminds the world that one person—even a peasant girl—can change the course of history.

:: Erika Schickel

Joan of Arc Selected Sources