I didn’t want to imitate anybody. Any movement I knew, I didn’t want to use.

—Pina Bausch

After World War II, modern dance was beginning to stretch its legs. Many dancers and choreographers felt confined by the strict movement vocabularies of Martha Graham and Lester Horton and the emphasis on expressionism and narrative. Dancers began to break out of the constraints of specific schools and explore new forms of movement.

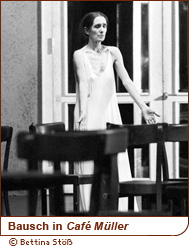

No one was more influential in ushering in the new era than modern-dance superstar Pina Bausch, who changed the landscape of dance and helped to found a new school known as Tanztheater, or dance-theater, a powerful combination of dance, theater, visual arts and music. Bausch created a solid repertoire of groundbreaking pieces, including her famed Café Müller (1978), about love and separation, and Kontakthof (Contact Yard, 1978), which explores male-female relations.

Bausch’s choreography is controversial, visually brilliant—and often shocking. But starting out, Bausch only wanted to be a dancer.

A Shy Child

Philippine Bausch was born on July 27, 1940, in the small industrial town of Solingen, Germany. Her siblings were much older, so she often played alone in her parents’ small restaurant. She danced constantly, playing under the tables, twirling and doing handstands. (Bausch’s Café Müller may have been inspired by this period of her life. The piece features dancers repeatedly running into the wall and around empty café tables and chairs.)

“I was afraid to speak,” Bausch said. “Dancing gave me a voice.” At age 14, she began to study dance at the Folkwang School in Essen. One of her teachers was the pioneering German Expressionist choreographer Kurt Jooss, who offered his students not just ballet classes, but lessons in costuming, photography, sculpture and design as well.

After graduating in 1958, Bausch headed for New York to take advantage of a scholarship to the Juilliard School. The timid Bausch had never been outside of Germany. She spoke no English and had little familiarity with big-city life, but she came alive in her dance classes.

She was as expressive as a dancer as she was reticent as a speaker. During her three years in New York, she was a principal member of Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer’s modern-dance troupe and she also danced for the more conventional Metropolitan Opera Ballet. But come 1962, her scholarship had run out, and it was time to head home.

A New Definition of Dance

Back in Germany, Bausch joined Jooss’ new Folkwang Ballet in the city of Essen, but she became frustrated. She “needed something to dance” and hadn’t found it yet. So Bausch choreographed two pieces herself: Fragmente (Fragment), featuring music by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, in 1968, and the award-winning Im Wind der Zeit (In the Wind of Time) in 1969. Her newfound passion for choreography came at a perfect time. When Jooss left the company in 1969, Bausch was pleased to take over his position as choreographer of the company.

She stayed at Folkwang until 1973, when she accepted a prestigious position as director of the Wuppertal Ballet in the sleepy town of Wuppertal, Germany, not far from Cologne. Thrilled at the chance to have full control over the company, she proceeded to completely revamp it.

Bausch replaced the Wuppertal’s classical ballets with her in-your-face blend of confessional intimacy and controversial dance-theater. She gave the performers snatches of dialogue and repetitive movements that recalled the movements of daily life. She put rage, fear, sexuality and hilarity—deep emotion—on the stage.

Facing the Opposition

Bausch involved herself in every aspect of her company’s operation, from the heating of the building to her dancers’ shoes. But Wuppertal was a conservative town, and, at first, the company suffered a backlash from an audience used to classical ballet.

“They would bang the doors and leave,” remembers dancer Meryl Tankard. “Once a man got up on stage and took a bucket of water I had as a prop and tried to throw it over one of the other dancers who was repeating a poem over and over. But she ducked and the water went all over the audience.”

Soon, though, the sleepy little town realized it had a superstar among its citizens. Dance luminaries and opera and theater directors began to make pilgrimages to Wuppertal to see Bausch’s work. She gained notoriety when she staged a movement sequence based on composer Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, and the company was eventually renamed the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. The rebel had won.

“She has basically reinvented dance,” said William Forsythe, director of the Frankfurt Ballet, in a 2002 interview with the Guardian. “She is one of the greatest innovators of the past 50 years ... She is a category of dance unto herself.”

Prime Time

Throughout her career, Bausch has dispensed with tradition in favor of a whirlwind of discovery in every performance. Today, her dancers are not your typical young and willowy ballet waifs; they are young, old, short, tall, skinny and stocky. And on stage, they are passionate, violent, confessional and intimately engaged with the audience. The stages themselves are covered with water, dirt or blankets of flowers. There is pop music, ambient sound, dancers playing instruments or sometimes no music at all.

Now in her 60s, Bausch is still a commanding, enigmatic and passionate dancer and choreographer. She has influenced two generations of performers, as well as opera, dance and theater directors. Thanks to dance, the shy and lonely German girl found her voice and took the world by storm.

:: Nora Pierce