Despite the fact that he is without invitation, a handsome, young stranger struts into the ballroom of King Louis XIV. The room, lit by brilliant candelabra, overflows with bejeweled noblewomen who are as rich as they are lovely. The revelers move in a lively waltz. The stranger takes only the most desired partners on his arm. He flirts with each, whispering proposals into their hot ears.

While propositioning a busty marquise, he spots a radiant ingenue surrounded by hopeful suitors. He brazenly enters their small circle and steals the girl away to the dance floor. Before they have completed their first turn around the ballroom, he has proposed several possible alternatives to dancing. Shaking off each proposal with only a move of her head, the girl provokes him to opt for a more persuasive argument. Pulling her close, he passionately kisses her on the mouth. She screams.

“Unhand her, rogue!” demands an outraged suitor, pushing the stranger aside and steadying the arm of the dazed mademoiselle. “Can you even imagine how a young girl feels after such an outrage?”

“Unhand her, rogue!” demands an outraged suitor, pushing the stranger aside and steadying the arm of the dazed mademoiselle. “Can you even imagine how a young girl feels after such an outrage?”

“I know quite a bit about how a young girl feels.”

“Swine.” The suitor places his hand on the hilt of his sword. Two men come to his side.

“Monsieurs, perhaps this matter would best be settled outside,” suggests one of the suitor’s noble friends.

The stranger snaps his heels together and bows smartly. “Excuse me, Mademoiselle. This will only take a minute.”

The young woman watches anxiously as the four men step out into the shadows. Outside, there is a calamitous clang of swords.

“Gently, now,” taunts the stranger to the first duelist. “It’s early in the night and I’m far from ready to retire.”

After a few more parries, the stranger tires of his eager opponent. “Now that’s enough,” he declares with a swift riposte. The first man falls to his knees and cries out in pain. The cry is heard inside, and the musicians fall silent. Within moments, two more such cries ring out.

The three heroic suitors down, the victor surveys the bloody scene. He leaves his victims’ still-warm bodies and returns to the party. All eyes are upon him as he emerges from the portico, red-tinged sword in hand. He gives his audience a cocky smile. A disinterested servant approaches, bearing a white handkerchief on a silver tray. The stranger wipes his blade clean and inserts it into his scabbard, returning the soiled cloth to the tray. He then follows the servant through the crowd.

Passing the astounded girl, the stranger nods curtly and winks.

The servant continues to the grandly appointed throne of the king. Facing Louis, the stranger removes the wig atop his head; long, auburn hair rolls down to his hips.

The king recognizes who is in his midst: “Mademoiselle Maupin, still up to your old tricks.”

The unmasked stranger curtsies deeply before her monarch.

“You are aware that I have outlawed duels with a penalty of death,” Louis says.

“There are certainly sweeter meetings than those found at a sword’s point,” La Maupin agrees.

Louis laughs at his fiery guest’s flippancy, and says, “But I do not think my decree mentions the possibility of a duel commandeered by a woman. So in this case, my female friend, I think it best you simply exit the party.”

La Maupin does. She knows that many more adventures involving sex and swords are to come.

Slingshots, Swords and Pistols

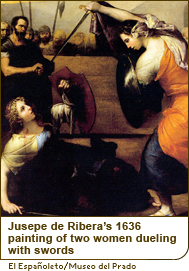

It’s difficult to document when women first started dueling, but some of the accounts of female duelists, like that of La Maupin, involve women disguised as men. Duels, it was commonly held, were the domain of men, and women who chose to settle disputes formally (sometimes to the death) often needed to cross-dress to do so.

It’s difficult to document when women first started dueling, but some of the accounts of female duelists, like that of La Maupin, involve women disguised as men. Duels, it was commonly held, were the domain of men, and women who chose to settle disputes formally (sometimes to the death) often needed to cross-dress to do so.

The earliest form of European dueling was the medieval judicial duel, or trial by battle, where if a man accused another of a crime, and the accused declared himself innocent, the two settled the ordeal in a duel (usually with swords). A judge established the place, weapon and time for the battle, and the outcome was accepted as the judgment of God. The judicial duel, which excluded only children and ecclesiastics, was practiced until the late 1500s. (Judicial duels remained legal in England until 1819, but unlike other European countries, England did not allow women to participate.)

After England’s King Henry II reformed the judicial system in favor of trials by jury, dueling was mostly used to privately settle disputes of honor among nobles throughout Europe. Winning duelists were often seen as heroes, and those who turned away from duels were considered inferior in character.

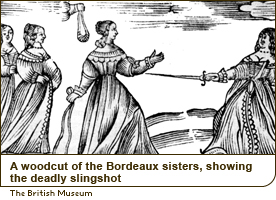

Eventually, some French aristocratic women began to participate in these fashionable fights. A so-called petticoat duel took place in 1650 between two women known as “the sisters of Bordeaux,” who fought over the merits of their respective husbands. One killed the other with a slingshot. The notion of women dueling was so scandalous that their names were omitted from records of the event to spare their families additional humiliation.

Eventually, some French aristocratic women began to participate in these fashionable fights. A so-called petticoat duel took place in 1650 between two women known as “the sisters of Bordeaux,” who fought over the merits of their respective husbands. One killed the other with a slingshot. The notion of women dueling was so scandalous that their names were omitted from records of the event to spare their families additional humiliation.

Petticoat duels weren’t common, but records do exist showing duels between women and duels between women and men over matters of love, honor and revenge. In 1552, two young women in Naples, Italy, met in a duel to fight over the love of a gentleman. In early 1700s France, two women dueled with pistols—once again to determine the true beloved of a particular man. Madame de Polignac exchanged fire with Madame de Nesle in the Bois de Boulogne. Madame de Nesle’s opening shot hit a tree branch above her, which came loose and fell on her opponent. Madame de Polignac had better aim: The ball from her gun stuck in Madame de Nesle’s corset, drawing a bit of blood from the woman’s left breast. Though both were injured, the wounds were slight and the women parted, neither worse for the wear.

The first recorded duel between English women took place in 1792 over an insult about age. Lady Almeria Braddock and Mrs. Elphinstone exchanged pistol shots at ten yards, missed each other and then concluded the event with smallswords. Upon drawing blood from Mrs. Elphinstone’s elbow, Lady Braddock declared her honor satisfied, and the two curtsied to each other and left the field. Witnesses agreed that the ladies conducted themselves with great courage and dignity.

In Liechtenstein in 1892, Princess Pauline Metternich and Countess Kielmannsegg engaged in the first recorded duel in which all parties involved, including the principals and their seconds, were female—and they dueled topless.

Duel Standards

Since at least 1041, various religious and most legal authorities have opposed dueling. For centuries, European kings issued anti-dueling edicts, but dueling continued to be practiced by men—and women dressed like them.

Because dueling primarily took place between two men of equal social status, a woman seeking to avenge her honor against a man had to dress as a man in order to fight one. One of the earliest cross-dressing duelists was recorded in the mid-1500s, during the reign of England’s Henry VIII. Wearing a doublet and satin hose and armed with a broadsword and buckler, Long Meg o’ Westminster soundly beat Sir James of Castile in London. She was later immortalized as Moll Frith in the play The Roaring Girl (1611) by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker. In the 1600s, a French woman, the Countess de Saint-Belmont, issued a challenge to a young cavalry officer who had camped out in her guest cottage without her permission. Upon accepting her challenge, which she signed as the Chevalier de Saint-Belmont, the cavalry officer showed up ready to fight a man. The countess quickly disarmed the officer and then revealed her true gender.

Because dueling primarily took place between two men of equal social status, a woman seeking to avenge her honor against a man had to dress as a man in order to fight one. One of the earliest cross-dressing duelists was recorded in the mid-1500s, during the reign of England’s Henry VIII. Wearing a doublet and satin hose and armed with a broadsword and buckler, Long Meg o’ Westminster soundly beat Sir James of Castile in London. She was later immortalized as Moll Frith in the play The Roaring Girl (1611) by Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker. In the 1600s, a French woman, the Countess de Saint-Belmont, issued a challenge to a young cavalry officer who had camped out in her guest cottage without her permission. Upon accepting her challenge, which she signed as the Chevalier de Saint-Belmont, the cavalry officer showed up ready to fight a man. The countess quickly disarmed the officer and then revealed her true gender.

While some female duelists only took up arms for an isolated incident, seeking to settle a dispute or complaint, other women made dueling more of a lifestyle. One of the most renowned of these adventuresses, a Basque woman known as the Lieutenant Nun, Catalina de Erauso, dueled her way across Latin America in the 1600s dressed so convincingly as a man that her own brother didn’t recognize her. Dressed as a man, pirate Mary Read reportedly fought a duel with another pirate on behalf of Read’s lover. In the midst of the swordplay, Read tore open her top to reveal her true sex. As her opponent’s attention was drawn to her chest, Read ran him through, killing him instantly. Alongside these real-life duelists, fictional adventuresses piqued the popular imagination of the time. The French playwright Molière’s favorite leading lady, Henriette-Sylvie, engaged another actress in a sword duel, both of them wearing masculine costumes.

:: Derek Ware

Duelists Selected Sources