We live in the wind and sand ... and our eyes are on the stars.

—WASP motto

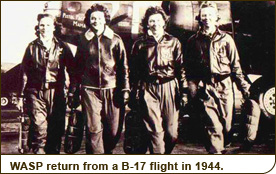

During World War II, a group of American women fought for the right to serve their country. These patriots weren’t content to simply follow Rosie the Riveter’s lead into the civilian workforce; they wanted to take to the skies and fly military airplanes. The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) endured much skepticism, grueling training and dangerous missions, all without the benefit of official military status. Yet these maverick women persevered, making a significant contribution to America’s war effort and to the future of military aviation. The WASP program proved that women were just as capable in the cockpit as men.

Women in the Air

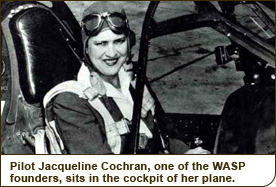

In the early months of World War II, two accomplished women pilots, Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love, proposed that the Army Air Forces train women pilots for military service. Neither pilot knew of the other’s suggestion, although both had the same idea: Women could take over ferrying missions and free male pilots for combat duty. Independently, both suggestions were rejected. At the time, there were plenty of male pilots and the military had no impetus to allow women to fly.

As the war raged on, military need trumped military mores and two separate units for female pilots were founded. Love headed the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), an experimental squadron of women pilots employed to ferry aircraft for the Air Transport Command (ATC), and Cochran led the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), the training program for the WAFS. In August 1943, the two groups were merged into one organization, the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

Earning Silver Wings

From 1943 to 1944, 25,000 women applied for the WASP training program. Of the 1,830 accepted, 1,074 would graduate. The cadets paid their own way to the training camp in Sweetwater, Texas, and were housed at the Bluebonnet Hotel. Later, the women lived six to a room in barracks at Avenger Field.

During training, the women wore surplus Army mechanics’ overalls, sizes 44 and up. Hairstyles and makeup quickly became obsolete thanks to the winds of west Texas and long days in training. Adding to the charms of the weather were the delights of the Texas wildlife: During a solo flight, one pilot looked onto her right wing and found a large rattlesnake inching towards her. Luckily, the slipstream caught the snake and it sailed off into the air. After this incident, all pilots checked their cockpits, especially for the first flight of the day.

There was no prouder day for a WASP trainee than her graduation day, when she received her official silver wings and was assigned to an operational unit. Each pilot purchased her uniform: khaki shirts and trousers for summer and Army green gabardine for winter. In spring 1944, the pilots were issued dress and flight uniforms in Santiago blue. The WASP were the first pilots of either gender to wear Air Force blues.

Of special pride to the women pilots was the WASP emblem, a winged sprite dubbed Fifinella. Leather patches bearing Fifinella’s image were sewn on WASP flight jackets.

Operational duties of the WASP were as varied as the women themselves. Some women ferried aircraft, others transported administrative officers or medical personnel. One pilot spent her free Sunday mornings flying a priest to remote Arizona Army bases so that Mass could be held. More dangerous missions included towing target sleeves for antiaircraft gunnery practice and test-hopping newly repaired or modified planes. WASP even flew B-26s and B-29s to prove to male pilots that these planes were safe to fly. The female pilots occasionally served as flight instructors and acted as copilots to male officers logging their required flight time.

Notably, the WASP were not militarized. Instead, their program was part of the U.S. Civil Service. This meant the women lacked military benefits such as health insurance and status as veterans. As members of a volunteer organization, WASP could resign at any time. Few did.

Sadly, 38 WASP and trainees were killed on missions. Because they were civilians, they did not receive the military escort and government-issued pine box provided for deceased male pilots. As a final affront, the American flag was not allowed to cover their coffins. Classmates, colleagues and friends took up collections to pay for their burials.

The Bold Experiment Ends

On December 20, 1944, the WASP program was deactivated. The women were told that they were no longer needed, as men were now available to do their jobs. The media, once supportive of the women, now turned against them. It seemed that no one wanted a woman “doing a man’s job” if a man was available.

The WASP returned to civilian life with no veterans’ benefits. In 1949, the Air Force offered military commissions—all in administrative and support positions—to all former WASP. Of the 1,074 pilots who had participated in the program, 115 accepted. Although 25 of them became career officers, they were never again permitted to fly military aircraft.

In 1972, former WASP met for a reunion. Talk turned to the injustices dealt them by the military. By the next reunion in 1974, they had formed a militarization committee. Three years of concerted political action paid off in 1977, when a law was passed to confer official military status on WASP service in World War II. Finally, these brave women were accorded their rightful place in history as veterans.

:: Maureen Russell

WASP Selected Sources