I am a woman who enjoyed herself very much; sometimes I lose, sometimes I win.

—Mata Hari

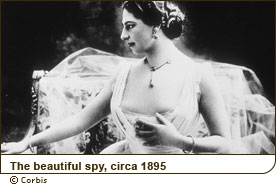

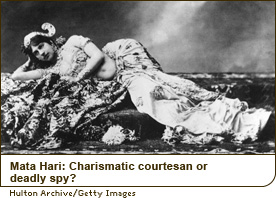

During World War I, the Allied army circulated posters that advised soldiers prone to loose lips and strong libidos to “keep mum, she’s not so dumb,” acknowledging the threat of female spies. Mata Hari, the most famous of femme fatales, was a sexy stripper-turned-operative who seduced men, stole secrets and was executed as a double agent for allegedly causing the deaths of 50,000 French soldiers.

Hari was a public figure, and her exotic persona made her an easy target for anti-spy propaganda during the tense time of war. In the years preceding World War I, she was Europe’s best-known courtesan, renown for her affairs with powerful military leaders. During the war, her unique position proved valuable for both French and German forces. The extent of her involvement in espionage on either side remains unclear, although most of the evidence attests that her spying activities were minor and, for the most part, unsuccessful. Nevertheless, she was sentenced to death and remains an enduring icon of intrigue and sexual power.

New Beginnings

Mata Hari began life as Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, the daughter of a wealthy hatmaker in the Netherlands. The girl had a normal bourgeois life until the death of her mother and abandonment by her father left her poor and alone. Eighteen-year-old Margaretha was forced to leave college (according to some for having an affair with the headmaster, although it’s more likely she couldn’t afford to stay in school). Desperate for financial security, she answered a lonely-hearts ad placed in an Amsterdam newspaper by an army captain. She and Captain Rudolph McLeod, who was 21 years her senior, shortly married and moved to the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) where he was stationed.

Though Southeast Asia’s exoticism excited Margaretha, her marriage quickly soured. Her rebellious sensuality and refusal to be matronly clashed with McLeod’s old-fashioned ideas about marriage. He became abusive and unfaithful; despite this, the couple had two children together. The tenuous marriage was finally done in by a horrific event—a nanny poisoned the children (rumors said the nanny was bribed by the husband of one of McLeod’s lovers). Margaretha’s young son died, and after nine years of unhappiness, Margaretha filed for divorce in 1904. She left her surviving daughter with relatives and headed to Paris to start a new life.

East Meets West

Margaretha, who had long fantasized about the glamour of Paris, embraced her newfound freedom. She worked a few odd jobs, but had little to offer except her beauty and natural grace. Wealthy men offered to sponsor her, but Margaretha had learned her lesson about relying upon a man for security. Since Orientalism was all the rage in Paris, Margaretha decided to cash in on her time abroad by becoming a “native” dancer. After a few attempts at renaming herself, she settled on Mata Hari (“sun of the day” in Malay) to honor the dawn of her new self.

In 1905, Mata Hari made her debut as a dancer at Madame Kireesvsky’s, a chic salon. Though she never studied dance, Hari had often watched the sultan of Jogja’s ballet dancers while in Java. She tailored the moves she remembered to suit Western tastes. Hari’s “Oriental” dance was hardly authentic, but it proved intoxicating to audiences, mostly because she embodied their fantasies about the exotic sensuality of Asian women. The city’s literary, artistic and scientific elite flocked to her performances. With her good looks and sexy subversion of taboos, it wasn’t long before Mata Hari became one of the highest-paid dancers in Europe, dancing on famous stages such as La Scala in Milan and Vienna’s Secession Art Hall.

Spy Mania

By the onset of World War I, Mata Hari was known throughout Europe. She traveled in luxury to major European cities and courted many high-profile men, including military officers and politicians. During this time, “spy mania” permeated the culture through films, novels and comics. Mata Hari’s glamorous lifestyle was particularly suspect, as she circulated in powerful social and military circles and could speak several languages. In 1915, British intelligence agents began to watch her. A year later, the French started keeping tabs on her as well.

By 1916, according to some sources, she was already knee-deep in German espionage. Others argue that she was merely a charismatic courtesan with many friends.

A Spy in the House of Love

The famous paramour then hit upon a serious occupational hazard: She fell in love with a young Russian captain named Vladimir de Masloff. She was ready to hang up her silk stockings and marry him, but because of mounting suspicions against her, the 40-year-old dancer was denied a pass to visit Vittel, where he was stationed. Hari solicited the help of Captain Georges Ladoux, head of the French espionage office. Ladoux was familiar with Hari’s reputation as a seductress, and though he’d heard the rumors about her possible affiliation with the Germans, he decided to make her a spy for the French. The record is hazy on Ladoux’s exact reason for hiring Hari; some now think he was framing her from the start. Either way, a deal was struck: In exchange for passage to Vittel and a million francs (about US$165,000), Mata Hari promised to seduce the crown prince of Germany.

Travel was extremely difficult at the time and Hari ended up stranded in Spain, with no word from Ladoux. She was now on her own. Undeterred, she made use of her time by locating a German attaché named Kalle and posing as a German agent to gather information from him.

She seduced Kalle, but her cover was blown when he caught her meeting with a French espionage attaché. Kalle sent a message to Berlin in a code he knew the Allies could read, identifying her as German agent H-21. Whether the message was true or not, Hari was revealed to the Allies as a German agent. Kalle then set her up again by “leaking” an insignificant rumor and paying her 3,500 pesetas (about US$700), which the Allies subsequently found. (She claimed Kalle paid her for amorous encounters.) When Mata Hari returned to Paris on January 13, 1917, two of Ladoux’s officers were waiting to follow her. On February 13, she was arrested at her hotel.

Last Dance

The French tried Hari as a double agent and sentenced her to death, despite inadequate evidence. She was the perfect scapegoat, a prominent figure whose punishment would serve as good propaganda for the French cause. Hari allegedly refused a blindfold, accepted a shot of rum and was killed by 11 shots. After she collapsed, a cavalry sergeant walked to her body and fired a shot into her temple.

Upon her death, the French erroneously claimed that Mata Hari was the most dangerous spy of all time. Though her spy work has proved relatively inconsequential, Mata Hari’s legacy as the quintessential femme fatale continues. Since 1920, more than 18 films have been made about the dancer, including one starring the glamorous Greta Garbo.

:: Kate Soto

Mata Hari Selected Sources