You put a roadblock in front of me and I’m going to find a way to get around it, over it, under it...or plow right through it if I have to.

—Picabo Street

Since she was a little girl, all Picabo Street ever wanted was to go—fast. And now, poised at the top of the super-G slope in Nagano, Japan, she can hardly bear the stillness as she waits to start. Never mind that she has neck pain and a headache that hasn’t gone away since a gruesome crash just weeks ago. And who cares that this isn’t even her main event? It’s the 1998 Olympics, and Street just wants to be bent-kneed and zooming down the course.

Since she was a little girl, all Picabo Street ever wanted was to go—fast. And now, poised at the top of the super-G slope in Nagano, Japan, she can hardly bear the stillness as she waits to start. Never mind that she has neck pain and a headache that hasn’t gone away since a gruesome crash just weeks ago. And who cares that this isn’t even her main event? It’s the 1998 Olympics, and Street just wants to be bent-kneed and zooming down the course.

Finally, she’s off.

She weaves at top speed between slaloms—and takes the gold.

The Prophecy of Baby Girl

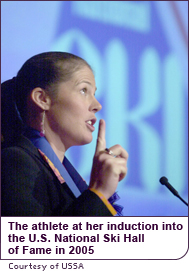

Every sport has its rebel, and downhill skiing is no exception. With a reputation for being both an outspoken maverick and a speed demon, Picabo Street has claimed her place in competitive-skiing history with two Olympic medals (silver, 1994; gold, 1998) and numerous World Cup victories. Her candor, resilience and spunk helped her win the adoration of fans, and her skill on the slopes established her reputation as one of the greatest skiers in U.S. women’s downhill history.

Born in 1971 to self-professed hippies Roland and Dee in Triumph, Idaho, Street was called Baby Girl until she was two. Her free-spirit parents had decided that they would let their children name themselves, but a trip to Mexico required a proper name on their daughter’s passport. They chose Picabo, the name of a nearby town, which means “shining waters” or “silver creek” in the Sho-Ban Indian language. As the only girl in a town with a population of 30, Street came naturally to competition, and fearlessness quickly defined her personality as she biked and wrestled with the boys. Dee says it was a challenge to keep her tomboy daughter safe because “she was never afraid of anything.” “[Competition] made me tough,” says Street, and that toughness would help propel her to the top of the skiing world.

Born in 1971 to self-professed hippies Roland and Dee in Triumph, Idaho, Street was called Baby Girl until she was two. Her free-spirit parents had decided that they would let their children name themselves, but a trip to Mexico required a proper name on their daughter’s passport. They chose Picabo, the name of a nearby town, which means “shining waters” or “silver creek” in the Sho-Ban Indian language. As the only girl in a town with a population of 30, Street came naturally to competition, and fearlessness quickly defined her personality as she biked and wrestled with the boys. Dee says it was a challenge to keep her tomboy daughter safe because “she was never afraid of anything.” “[Competition] made me tough,” says Street, and that toughness would help propel her to the top of the skiing world.

Peak This

Street was born a speed demon. “My dad and my brother used to go skiing and leave me at home,” she told woa.tv. “Finally I threw my weight around enough for them to take me. And the first time I went I was completely fearless...all I wanted to do was go faster, faster, faster.”

Although the five-year-old Street initially began racing down hills to catch her brother, Baba, she turned to official races at age 10, competing with children who were older and usually wealthier. The Street family was poor, and pricey accessories and equipment were out of reach for the young racer. Despite this, her talent on the slopes became apparent.

Street made it to the U.S. junior ski team at 15. In short order, she won the national junior championships in downhill and super–giant (super–G) slaloms. By the late eighties, her coaches decided she was ready for the U.S. ski team. She quickly developed a reputation for sassiness and ignored curfew rules. According to one of her coaches, Street would “never win because she can’t follow the rules.” Attributing her defiance to a dislike for authority, perhaps inherited from her parents’ counterculture lifestyle, Street told Sporting News: “I never liked being in the dark. With the team, it was always do this, do that. I felt I was always in the dark.”

In 1990 Street was suspended from the team for lack of discipline, a rebellious attitude and being overweight and out of shape. She would have to step up her game if she wanted to ski seriously. Her strength on the slopes was indisputable, but her autonomous attitude wasn’t conducive to following the coaches’ strict directions and the rules of the slope.

According to Street, “[Getting kicked off the team] woke me up.” Her father, a stonemason, was working in Hawaii at the time and talked his daughter into joining him. Convinced that she could still succeed in skiing, he put her through the athlete’s equivalent of boot camp. “I did sit-ups and push-ups morning and night to earn my food,” she

told woa.tv. "And I didn’t talk on the phone; I didn’t go out with my friends. I ate really well. I trained absurdly.” It

worked. Street won back her place on the team within the

year.

According to Street, “[Getting kicked off the team] woke me up.” Her father, a stonemason, was working in Hawaii at the time and talked his daughter into joining him. Convinced that she could still succeed in skiing, he put her through the athlete’s equivalent of boot camp. “I did sit-ups and push-ups morning and night to earn my food,” she

told woa.tv. "And I didn’t talk on the phone; I didn’t go out with my friends. I ate really well. I trained absurdly.” It

worked. Street won back her place on the team within the

year.

She scored her first international victory in 1993, when she won a silver medal in combined downhill and slalom at the world championships in Japan. A year later, she won a silver medal in downhill at the 1994 Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway. Then, in 1995, she surpassed not only herself but every other U.S. skier in history: She became the first American to win the World Cup women’s downhill championship, winning six out of nine downhill races. She dominated the world of women’s skiing, racing down hills at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour (or 128.7 kilometers per hour) in little more than spandex and a helmet.

Street experienced another amazing victory in 1996, when she won another women’s downhill. It seemed as if there was no stopping the speed demon.

But in December of that year, Street suffered a terrible setback when she crashed on a training course in Vail, Colorado. She tore the anterior cruciate ligament in her left knee, broke her femur and pulled her calf muscle off the bone. Six months later, after undergoing reconstructive surgery as well as intensive physical therapy, Street remained hopeful: “I think I’m going to be as strong or stronger than ever before.”

But in December of that year, Street suffered a terrible setback when she crashed on a training course in Vail, Colorado. She tore the anterior cruciate ligament in her left knee, broke her femur and pulled her calf muscle off the bone. Six months later, after undergoing reconstructive surgery as well as intensive physical therapy, Street remained hopeful: “I think I’m going to be as strong or stronger than ever before.”

She got back on the slopes and then, one week before the 1998 Olympic Games, Street crashed into a fence on the slopes in Are, Sweden. She was knocked out for several minutes and badly bruised. But she walked away from the concussion and, two weeks later, arrived at the Games in Nagano, Japan, where she competed in the super–G and won the gold medal.

Uphill Battles

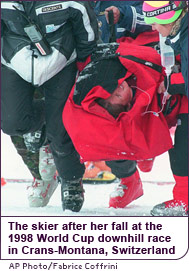

In 1998, less than a month after winning a gold medal, Street crashed a third time, slamming into a safety fence at a World Cup event in Crans–Montana, Switzerland. This time, she broke her leg in nine different places. Her recovery would require multiple surgeries, put her out of competition for over a year and force the fastest woman on skis to relearn how to walk.

The surgeries rendered Street bedridden for six months. The thought of retirement was in the air. “I can’t deny how insanely human I feel now after this,” she said in an interview with USA Today. “I don’t feel invincible anymore.“ Fears of further—and even more devastating—injuries crept up on Street, inspiring thoughts of quitting. But she transcended her fear. As she told woa.tv , “Something inside me said, ‘No, you have to get back to familiar territory. And your familiar territory happens to be world–class downhill.’”

The surgeries rendered Street bedridden for six months. The thought of retirement was in the air. “I can’t deny how insanely human I feel now after this,” she said in an interview with USA Today. “I don’t feel invincible anymore.“ Fears of further—and even more devastating—injuries crept up on Street, inspiring thoughts of quitting. But she transcended her fear. As she told woa.tv , “Something inside me said, ‘No, you have to get back to familiar territory. And your familiar territory happens to be world–class downhill.’”

A few years later, she was the leading downhill qualifier for the 2002 U.S. Olympic ski team, but she finished in 16th place in women’s downhill. Although fans cheered her on, she decided to retire. In November 2002, she took a ceremonial final run down the World Cup course in Park City, Utah, and then cried as she watched a video of career highlights—her gold medal in Nagano and her horrible crashes—while surrounded by friends and family.

Even though she retired at the youthful age of 31, Street has kept herself busy. She founded her own nonprofit, Picabo’s Street of Dreams Foundation, Inc., to support young people in sports. She has had TV assignments with CBS Sports and other networks; written her autobiography, Picabo: Nothing to Hide (McGraw–Hill Companies, 2002); and had a baby.

Street’s thoughts on her legacy reflect the open attitude she brought to a very competitive sport. “I like to think I perpetuated sportsmanship and camaraderie, and that expressing yourself is part of the deal. Showing your emotions, that’s okay. Your fans will love you more for it.” To this list, she could add tenacity, determination in the face of major roadblocks and bravery. Street gave the sport of alpine skiing a human face and is frequently referred to as an Olympic hero. Triumph isn’t just the name of her hometown—one could say it was her motto.

:: woa.tv staff

Read More About Picabo Street