I approached the sport like there wasn’t a gender issue,

and I wouldn’t participate in the mind-set of “she is just

a girl.”

—Julie Krone

A field of Thoroughbreds streaks down the track at speeds close to 40 miles (64 kilometers) per hour. It’s 1993, and the competitors are at the top of the stretch at the Saratoga Race Course in New York. A diminutive female figure smoothly maneuvers her horse, Seattle Way, into the middle of the pack, positioning for the win.

Suddenly, another horse veers into her path. In an instant, legs tangle, horses scream. Seattle Way stumbles, launching the tiny jockey onto the track, right in the path of the thundering racers. She bounces into a sitting position, and then, in an instant, is trampled like a rag doll by deadly hooves. Anklebones shatter, ribs crack. A crushing blow directly to her heart. As ambulance sirens wail, the woman’s crumpled body lies motionless.

Miraculously, doctors are able to save the woman’s life, despite her crushed body. But it will take more than a miracle to save the woman’s career as a jockey.

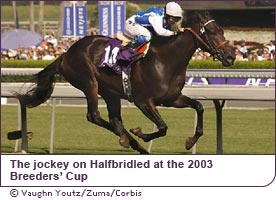

But this particular jockey is Julie Krone, and undaunted, only nine months later she begins an incredible comeback. Overcoming multiple severe injuries, Krone’s sheer determination will lead her to achieve a series of major victories, including a historic win at the 2003 Breeders’ Cup at the age of 40.

Small Package, Big Talent

The daughter of an art teacher and a former equestrian

champion, high-spirited Julie Krone was on horseback by

the age of two. By three, she was taking her own horse

on 5-mile (8.1-kilometer) rides. She won her first

18-and-under event at age five, and at 13, she knew she

wanted to become a jockey.

The daughter of an art teacher and a former equestrian

champion, high-spirited Julie Krone was on horseback by

the age of two. By three, she was taking her own horse

on 5-mile (8.1-kilometer) rides. She won her first

18-and-under event at age five, and at 13, she knew she

wanted to become a jockey.

Krone had an unconventional childhood. She and her older brother, Donnie, were encouraged to take risks and were left largely unsupervised. The family rarely ate dinner together, and there was often little food in the house. Krone sometimes ate dog food with the family’s dogs because her parents were preoccupied with other interests. When she was 15, her parents divorced.

At the end of her sophomore year in high school, Krone went to Churchill Downs in Kentucky with a fake birth certificate to work as a groom and exercise rider for three months. Bitten by the racing bug, she dropped out of high school halfway through her senior year and moved to Florida to live with her grandparents and work as an exercise rider and apprentice jockey at Tampa Bay Downs. The guards, thinking the 4-foot-10-inch, 100-pound (147-centimeter, 45-kilogram) blond with the high-pitched voice was a little girl, turned her away at the gates. Undaunted, she climbed over the fence. Trainer Jerry Pace liked her determination and decided to let her ride. To his surprise, on February 12, 1981, on her 11th mount, a 17-year-old Krone rode her first winner, Lord Farkle, at Tampa Bay Downs. She won eight more times in her first 48 races, working her way up the ranks.

Riding Into the Record Books

Though horse racing is traditionally a male-dominated

sport, Krone established herself by proving that brute

strength wasn’t always the key to winning a race. Whereas

many male riders force their horses with strong whip motions,

Krone exhibited a natural ability to communicate with her

horses. With her strong hands, she could gently guide the

longest shot into the winner’s circle. Off the track, Krone

used a combination of girlish charm and toughness to gain

acceptance from the other jockeys. Given her series of

wins, her talent as a jockey could not be denied.

Though horse racing is traditionally a male-dominated

sport, Krone established herself by proving that brute

strength wasn’t always the key to winning a race. Whereas

many male riders force their horses with strong whip motions,

Krone exhibited a natural ability to communicate with her

horses. With her strong hands, she could gently guide the

longest shot into the winner’s circle. Off the track, Krone

used a combination of girlish charm and toughness to gain

acceptance from the other jockeys. Given her series of

wins, her talent as a jockey could not be denied.

Unsurprisingly, Krone had a wild streak. She drove her red Porsche at high speeds, even affixing a wood block to the accelerator so she could push the pedal to the metal. In 1983, authorities at a race in Maryland found marijuana in her car. The 20-year-old Krone was suspended from racing for 60 days. Devastated, she immediately got herself clean.

Upon her return to racing, she thrived. In 1987, she became the first female to win a meeting title at a major track for leading at Monmouth Park in New Jersey with 130 wins. In 1992 and 1993, she won meeting titles against the top East Coast jockeys at Florida’s Gulfstream Park.

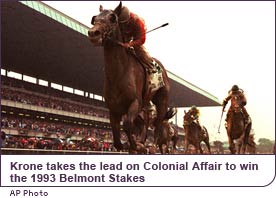

Next up was the Belmont, one of the legs of the Triple

Crown, where she won the meeting title astride long shot

Colonial Affair in 1993. The first woman to ever win a Triple Crown race, her winning ride was described

in Sports Illustrated as “showing the patience,

intelligence and tactical savvy that have made her one

of the nation’s leading performers in a game long dominated

by men.” Soon after, ESPN named her the year’s top female

athlete. She was living her dreams.

Next up was the Belmont, one of the legs of the Triple

Crown, where she won the meeting title astride long shot

Colonial Affair in 1993. The first woman to ever win a Triple Crown race, her winning ride was described

in Sports Illustrated as “showing the patience,

intelligence and tactical savvy that have made her one

of the nation’s leading performers in a game long dominated

by men.” Soon after, ESPN named her the year’s top female

athlete. She was living her dreams.

Pain and Triumph

You risk life and limb to share a relationship with

a Thoroughbred. You go down the stretch and push on his

neck and feel his desire to win is the same as yours.

—Julie Krone

Just two months after her Belmont victory, Krone was involved in a horrible accident at Saratoga that threatened to end her career. Her ankle was so badly crushed that it required two steel plates and 14 screws to repair. She also suffered a cardiac contusion so severe that she would have died if it weren’t for her protective vest. Although doctors said she wouldn’t be able to ride again for at least a year, she fought hard. “I spent years trying to show how tough a rider I was,” she wrote in her 1995 autobiography, Riding for My Life(Little, Brown & Co.). “To show any weakness felt like failure to me.” After nine months of determined rehabilitation, she made a comeback.

But in January 1996, Krone went down again, fracturing both of her hands at Florida’s Gulfstream Park. This time, the mental wounds were severe. She lost her nerve and was plagued with nightmares. Her winning streak was over. She contemplated suicide.

In the summer of 1996, a psychiatrist diagnosed Krone

with post-traumatic stress disorder. With therapy and medication,

she slowly began winning again, and in 1998 she finished

second in the jockey standings at Monmouth Park.

In the summer of 1996, a psychiatrist diagnosed Krone

with post-traumatic stress disorder. With therapy and medication,

she slowly began winning again, and in 1998 she finished

second in the jockey standings at Monmouth Park.

On April 18, 1999, she rode three winning horses and two seconds. And then she retired, with 3,545 victories and more than US$81 million in lifetime earnings to her credit.

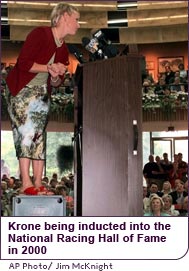

In 2000, Krone became the first female jockey enshrined in the National Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame. During her acceptance speech, she said, "I want this to be a lesson to all kids everywhere. If the stable gate is closed, climb the fence."

A Last Hurrah

Krone surprised everyone when she came out of retirement in November 2002. She promptly won 20 races. But then, in March 2003, she fractured two backbones and suffered three compressed vertebrae in a fall at California’s Santa Anita Park.

Just months later, she came back again to win

eight stakes—among them two Grade I races—at the Del Mar

Thoroughbred Club in California. She took the top prize

of the summer season, the US$1 million Pacific Classic.

But she was just getting warmed up. That October, Krone

made history as the first woman to win a Breeders’ Cup

race.

A mere two months after that historic victory, Krone was thrown from her horse in a two-horse collision that left her with two fractured ribs. During her recuperation, she was named one of USA Today’s ten toughest athletes.

Today, Krone is the proud mother of a beautiful baby girl, Loralei. She and her husband, racing writer Jay Hovdey, live in Encinitas, California, where Krone still finds the time to bond with her horse, Miss Piggy, and occasionally surf the waves. Amazingly, with all of the injuries she has sustained over the years, Krone experiences no residual pain. Though she has retired from professional racing, she continues to ride with the same grace and youthful agility that marked her extraordinary career.

:: Lisa Cooke

Read More About Julie Krone