Women fly planes, fight wars and go on safaris; what’s so different about fighting bulls?

—Ángela Hernández, bullfighter

Mexico, 1940. An 18-year-old girl wearing a dark wide-brimmed hat stands alone in the sun. The wind plays in her cape, but she stands perfectly still, letting her partner make the first move.

He is called Chiclanero and he only has eyes for her. Ten times her size, the muscular Bos taurus ibericus was born and bred for this moment. The desire to kill her consumes him. He breathes heavily, pawing the dirt, as she leads him on a chase that will only end one way for him. Her own fate is not so clear.

A level head and youthful agility are her best weapons. Boldly, she swirls her cape high over her head with both hands, thrilling the crowd.  At the peak of her bravado, however, her luck runs out. Sharp horns penetrate her flesh, leaving a deep wound, causing the young woman to faint.

At the peak of her bravado, however, her luck runs out. Sharp horns penetrate her flesh, leaving a deep wound, causing the young woman to faint.

She comes to in the bullring’s infirmary as she is being prepped for emergency surgery. Pushing the surgeons aside, the girl bolts back to the ring, where Chiclanero can still smell her blood. Only one impassioned sword thrust is needed to take down the bull. The exhausted bullfighter hits her target, and when she finally collapses, it is with the defeated animal’s ears gripped in each of her slender hands.

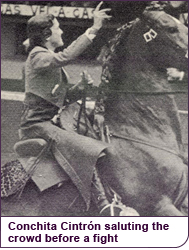

Later, Conchita Cintrón would say of the event, “I was really quite happy ... because I finally knew what it felt like to be gored.”

From France to Latin America, in pants and in skirts, on horseback and on foot, courageous women have pitted themselves against charging bulls for centuries—and have fought obstacles larger than bulls to do so.

Stepping Into the Plaza

For centuries, women bullfighters have existed in Spain. In the 1700s, there was María de Gaucín, a nun who left her convent to become a torera. Around the same time, Nicolasa Escamilla, better known as La Pajuelera (The Match-Seller), became the first celebrity torera. She was immortalized in a drawing by Goya and described by a writer of her time, priest and author Father Martín Sarmiento, as “the disgrace of the devout, compassionate female sex.”

La Pajuelera and other toreras of her day were allowed to perform only at the whim of local authorities. It was Joseph Bonaparte, aka King José I of Spain (1768–1844), who first gave the royal blessing to womanly bullfights in 1808, opening up the nineteenth century to a few dozen toreras. While many men considered women’s performances comedy, these corridas were just as deadly as the masculine variety—perhaps more so, since women performed in dangerously restricting frilly dresses and had limited opportunities to practice their art. Only the aptly named La Fragosa (She Who Creates an Uproar), Dolores Sánchez, had the bravado to shock the masses by appearing in the traditional male attire, the traje de luces.

This relatively open era in terms of women’s participation lasted only a hundred years, for Spain passed edicts in 1908 and 1930 banning women from bullfighting. The many Spanish toreras working at the time had to retire or emigrate to more welcoming Latin America. Cross-dressing torera La Reverte (or María Salomé Rodríguez Tripiona) chose a third option: She claimed never to have been a woman in the first place.

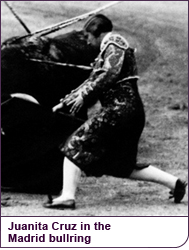

In 1934, Juanita Cruz, who became the world’s first full-fledged matadora, succeeded in petitioning the government of the new Spanish Republic for permission to perform, which she did until the Spanish Civil War began in 1936. Then she emigrated to Mexico, as Francisco Franco closed the doors on women bullfighters once more.

In 1934, Juanita Cruz, who became the world’s first full-fledged matadora, succeeded in petitioning the government of the new Spanish Republic for permission to perform, which she did until the Spanish Civil War began in 1936. Then she emigrated to Mexico, as Francisco Franco closed the doors on women bullfighters once more.

Off Her High Horse

For much of the twentieth century, Latin America was the hot spot for face-offs between women and bulls. Women headed there from the United States, Germany, Hungary and even China. While each country produced a few stars, Peruvian American Conchita Cintrón is the undisputed superstar of Latin America. A contemporary of Juanita Cruz, Cintrón flew directly in the face of Franco, the people of Spain and a bull the day she dismounted her horse in Jaén and fought a Spanish bull on foot in 1949.

Facing a bull on or off a horse has been a key distinction for twentieth-century toreras. Rejoneo, mounted bullfighting, is the oldest form of toreo, and while Spanish law has on several occasions forbidden women to face bulls on foot, rejoneo has more frequently been open to women. For this reason, rejoneadora Cintrón was able to perform in Spain in the years when matadora Cruz was not. The idea of a woman standing nose to nose with a bull seems to have been more than some authorities could take. (Cintrón was arrested, when she violated the prohibition during her corrida in Jaén.) A woman on horseback in a nonaggressive activity, on the other hand, is called an amazona in Spanish and admired as presenting an ideal image of womanhood.

Practically, while rejoneo can be just as dangerous, the rejoneadora does enjoy a height advantage that the matadora does not, and height is often cited as a disadvantage for women in bullfighting. Another is forearm strength: Holding out a sword under a muleta quickly makes an arm throb. Still, bullfighting is not a sport that requires a bulky physique; a lithe matadora is as likely to evade a rushing bull as is a matador.

All of these physical considerations were addressed by Ángela Hernández, a Spanish novillera, in her three-year battle with the Spanish Supreme Court, which finally resulted in the 1974 lifting of the ban on matadoras, and a legal precedent allowing Spanish women to pursue any career they choose. The door was open once again.

Facing the Bull

Today, women have the same legal rights as men in the ring, but the path to becoming a matadora is still paved with chauvinism. Cristina Sánchez once faced all the bulls in a corrida on her own, because no men wanted to share the ring with her. And while Ángela Hernández received support for her efforts from some male bullfighters, others refused to perform with her.

Moreover, women’s presence in the ring has been too sporadic to allow for much mentoring between experienced and novice matadoras. Women wanting to fight bulls have mostly been dependent upon men willing to share their knowledge, and only those fortunate enough to find supportive male mentors (often in their own families) have succeeded.

The first step in the official process is practicing as a becerrista, fighting one-year-old calves (becerros). Success leads to working as a novillera, who fights novillos, or two- and three-year-old bulls. The next goal is a milestone ceremony known as the alternativa, in which a full-fledged matador offers a novillera the opportunity to fight one of his two scheduled bulls that day. That matador is considered the novillera’s padrino, or godfather. So far, there has only been one instance of a matadora sponsoring another matadora at her alternativa: In 1997, in Cáceres, Spain, Cristina Sánchez served as madrina (godmother) to María Paz Vega, a young bullfighter who still is active in the sport today. Vega thus became the first woman to take her alternativa in Spain, and the first sponsored by another woman.

The first step in the official process is practicing as a becerrista, fighting one-year-old calves (becerros). Success leads to working as a novillera, who fights novillos, or two- and three-year-old bulls. The next goal is a milestone ceremony known as the alternativa, in which a full-fledged matador offers a novillera the opportunity to fight one of his two scheduled bulls that day. That matador is considered the novillera’s padrino, or godfather. So far, there has only been one instance of a matadora sponsoring another matadora at her alternativa: In 1997, in Cáceres, Spain, Cristina Sánchez served as madrina (godmother) to María Paz Vega, a young bullfighter who still is active in the sport today. Vega thus became the first woman to take her alternativa in Spain, and the first sponsored by another woman.

Although the sport is popular in France, Portugal and throughout Latin America, Spain remains the mecca of bullfighting. Las Ventas in Madrid is the bullring with the most prestige, and to date no woman has taken her alternativa there. Most have taken their alternativas in Mexico; Cristina Sánchez was the first woman to take hers in Europe on May 25, 1996, at Nîmes, France.

The Tradition Lives On

In recent years, women bullfighters have increasingly come together. In 2003, three women performed on a bill together in Mexico: Mexican novilleras Hilda Tenorio and Marbella Romero performed with Spanish novillera Raquel Sánchez. French rejoneadora Maria Sara was honored at her 1991 alternativa with an appearance by Conchita Cintrón. In 2005, María Paz Vega performed as matadora at the esteemed Las Ventas ring, confirming the status Cristina Sánchez had shared with her in 1997.

While bullfighting is still extremely male-dominated, women bullfighters are on the rise and are increasingly accepted by fans. The 2002 Spanish film Hable con ella (Talk to Her), by celebrated director Pedro Almodóvar, was an international box-office success with its story of a powerful, sexy woman bullfighter getting gored during a particularly daring move known as larga cambiada a porta gayola: She got down on one knee and opened up her arms, directly in front of the gate just before the bull was released into the ring. The character could have been based on any one of the gutsy women currently in the ring.

While bullfighting is still extremely male-dominated, women bullfighters are on the rise and are increasingly accepted by fans. The 2002 Spanish film Hable con ella (Talk to Her), by celebrated director Pedro Almodóvar, was an international box-office success with its story of a powerful, sexy woman bullfighter getting gored during a particularly daring move known as larga cambiada a porta gayola: She got down on one knee and opened up her arms, directly in front of the gate just before the bull was released into the ring. The character could have been based on any one of the gutsy women currently in the ring.

Women bullfighters have overcome laws excluding them, clothing restricting them and men refusing to share a bullring with them. They have continued to enter the bullring, bedazzling audiences and vanquishing bulls with style and skill.

:: Roberta Brown

Read More About Bullfighting