The history of women’s boxing is difficult to chart because many bouts took place without institutional sanctions. Though boxing originated in ancient Greece, the first reported match between women was not until the 1700s, and the sport has grown in spurts since then. Though the 1904 Olympics featured women’s boxing, it was only a display event and the sport hasn’t returned to the Games since (although there is talk of adding it to the roster for 2008). During the fitness boom of the 1980s, boxing went mainstream and became a popular form of exercise for women.

Fighting to Enter the Ring

Various exhibitions occurred in the first half of the twentieth century, but these bouts were mostly novelty acts, with participants kicking, scratching and throwing. The sport gained some respect in the 1950s when fighters such as Barbara Buttrick, JoAnn Hagen and Phyllis Kugler staged a series of professional matches. At the time, women’s bouts were much shorter than men’s and women often fought men in exhibition matches.

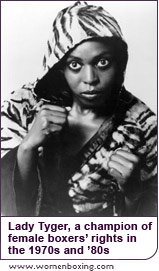

The boxing establishment’s chauvinism led to a serious of legal battles in the 1970s as women fighters such as Caroline Svendsen, Cathy “Cat” Davis, Jackie Tonawanda and Marion “Lady Tyger” Trimiar sued to receive their boxing licenses. The plight of professional women fighters was again in the news when Trimiar started a hunger strike in 1987 to protest the poor treatment and pay of her colleagues.

The boxing establishment’s chauvinism led to a serious of legal battles in the 1970s as women fighters such as Caroline Svendsen, Cathy “Cat” Davis, Jackie Tonawanda and Marion “Lady Tyger” Trimiar sued to receive their boxing licenses. The plight of professional women fighters was again in the news when Trimiar started a hunger strike in 1987 to protest the poor treatment and pay of her colleagues.

Modern-day boxing stars such as Christy Martin, Stella Nijhof, Krysti Rosario and Laila Ali owe much to these forerunners. The AIBA finally sanctioned women’s amateur boxing in 1994. Today, women fight in the major venues—Madison Square Garden and Caesars Palace—though still on the undercards of multimillion-dollar events. There are 18 professional weight classes and 15 weight classes in amateur or Olympic-style competition. The rules of a bout are slightly different than men’s boxing in term of the length of rounds. Also, women use breast protectors but groin protection (standard in the men’s sport) is optional. To compete, female boxers must sign a waiver stating that they are not pregnant.

In 2001, Laila Ali and Jacqui Frazier-Lyde (daughters of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier), fought before a live crowd of eight thousand and more than one hundred thousand pay-per-viewers. The unprecedented media coverage heightened the profile of women’s boxing. In eight aggressive rounds, both the boxers exchanged solid punches, but when the bell rang it was Ali who won the victory.

Despite the increased exposure, professional women’s boxing continues to struggle to find enough contenders in each weight division and marquee names. It’s been an uphill battle for female boxers, but they won’t back down. As Laila Ali told ESPN in a 2003 interview, “What I have to work at is getting my respect as a fighter, and not just a female fighter. I want to be a good fighter.”

But fighting may not be the first thing the average woman thinks of when she walks into a boxing class. As women look for new ways to get in shape, boxing’s virtues quickly become apparent. Unlike Pilates and other low-impact forms of exercise, boxing allows women to develop qualities that have traditionally been associated with men-physical power, purposeful aggression and speed. Throw in the development of hand-eye coordination, balance, agility and muscle mass, and it’s easy to understand why many women are inspired by the way Hilary Swank transformed her body for Million Dollar Baby (2004). For many women, feeling powerful and confident, both physically and mentally, is an irresistible benefit of boxing. From world-title bouts to classes at the local fitness center, the sport encourages female fighters of all types to throw punches and get in shape.

:: Ben Cohen